The status of Yellow-browed Warbler in the West Midlands Region and a comparison with Siberian Chiffchaff

|

The status of Yellow-browed Warbler in the West Midlands Region and a comparison with Siberian Chiffchaff |

This paper was first published in the West Midland Bird Club's Annual Report No. 89, for 2022 (published 2024). It is reproduced here with minor amendments.

In particular, the number of

records for 2022 has been updated from four to five and hence the regional total

for 1986 - 2022 from 59 to 60.

An additional record from Warwickshire in

late October 2022 seemingly did not reach the county recorder for over three

months after the

observation

and thus missed the preparation and submission of the printed version of the

paper.

The recommended citation for this paper is thus that for the online version, as at the foot of this text.

Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus, trapped

at Sandwell Valley, West Midlands, on September 23rd, 2008.

Photo: Pete Hackett.

The breeding range of Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus extends from the northern Urals east across Siberia to the Sea of Okhotsk and south to the northern Sayan mountains (Cramp et al. 1992). The traditional wintering range lies in SE Asia, from Afghanistan, Nepal and Bangladesh east to SE China and south to the Malay peninsula. Thus, at their nearest points, the breeding and wintering ranges lie 3500 km and 6000 km, respectively, from Britain. It is no surprise that, historically, Yellow-browed Warblers occurred relatively rarely in the British Isles. The first record in Britain was in Northumberland in September 1838 (Brown & Grice 2005). By the time of the Handbook of British Birds (Witherby et al. 1938), the species was regarded as a fairly regular visitor in autumn to Fair Isle but, elsewhere in Britain, only about 130 individuals were documented. Sharrock (1974) noted a total of 147 in the nine years 1958 - 1966, while numbers per annum in these nine years varied between three and 31. Then, in 1967, 128 were recorded in the British Isles, a total which Sharrock described as an invasion but which was to be dwarfed by the totals reaching Britain in the decades to come. Baker & Catley (1987) documented an annual mean of 77 between 1968 and 1975, increasing to 101 between 1976 and 1983. Dymond et al. (1989) indicated that over 1500 occurred in Britain and Ireland between 1980 and 1985, with nearly 1000 in 1984/1985 alone. The annual Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain, published in British Birds, listed annual means of 328 during 1990 - 99, 749 during 2000 - 09 and 1935 during 2010 - 2017 (White & Kehoe 2019). This exponential growth during the new millennium culminated in a record annual total of 4050 during 2016. Numbers fell back to c.1950 in 2017 but this was still the fourth highest annual total on record. With numbers then becoming too large for accurate assessments in several key regions (such as Shetland, Norfolk and Scilly), the species was no longer included in the Scarce Migrants reports after 2017 but a grand total of c.30,700 was estimated for the period 1968 - 2017 as a whole (White & Kehoe 2019). Thus, one of the more remarkable ornithological events of recent decades has been the transformation in the status of Yellow-browed Warbler from rarity to annual visitor in significant numbers. This dramatic increase has been mirrored across western Europe. Dufour et al. (2022) wrote: ‘In Europe, the Yellow-browed Warbler has become a regular autumn visitor in the last 30 years along the western European flyway, with thousands of birds occurring each autumn on a large front from Scandinavia to the Iberian Peninsula.’

The vast majority of Yellow-browed Warblers reaching Britain are recorded between mid-September and late-November. In 2017, for example, 97% were recorded during September to November, with just 2.2% during the winter (December, January and February) and 0.8% during the spring (March to May) (White & Kehoe 2019). Most individuals recorded in winter are on the south coast of England (in 2013, for example, 31 of 42 (74%) were in either Cornwall or Devon).

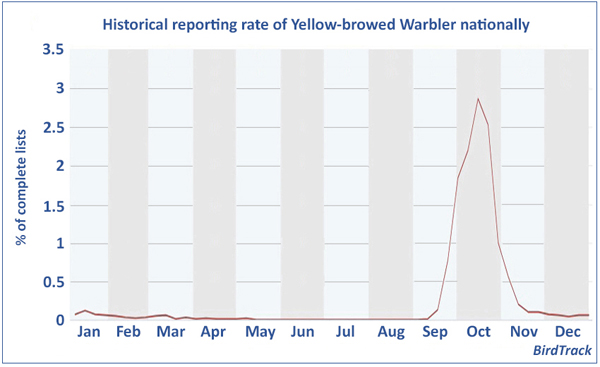

The typical monthly profile in Britain is illustrated by the historical reporting rate and peak counts on the BTO’s BirdTrack website (Figures 1 and 2, reproduced with permission from the BTO).

Figure 1. The historical national reporting rate for Yellow-browed Warbler, from the BTO’s BirdTrack.

(Reproduced with permission of the BTO.)

Figure 1 shows the national distribution of reports by week of occurrence, with a peak in mid-October. However, the numbers of individuals in the BirdTrack database have peaked somewhat earlier, in mid- to late-September (Figure 2). This no doubt reflects the high numbers (35% of the national total in 2013) reported from the Northern Isles, especially Shetland, where arrivals tend to be slightly earlier than farther south in England.

Figure 2. Historical peak counts of Yellow-browed Warbler by week, adapted from the BTO’s Birdtrack. (Reproduced with permission of the BTO.)

Despite vastly increased numbers reaching Britain, most still occur at or near the coast. In 2013, 75% of the national total in combination occurred in the Northern Isles (35%), the English east coast (26%) and SW England (14%) (White & Kehoe 2016). However, the species is now widely distributed, with small numbers found even well inland.

The following text examines the evolving status of Yellow-browed Warbler in the West Midlands Region, set within this national context. Accredited records have been extracted from the WMBC Annual Reports. Reports appearing on news-lines but for which county recorders have not received supporting details are not included.

The first Yellow-browed Warbler to be recorded in the West Midlands Region was at Upton Warren, Worcestershire, on October 8th 1986. By 2001, fifteen years later, just five further individuals had been recorded (The new Birds of the West Midlands, Harrison & Harrison 2005). The following 21 years, however, produced an additional 54 individuals, escalating the regional total to 60 by 2022.

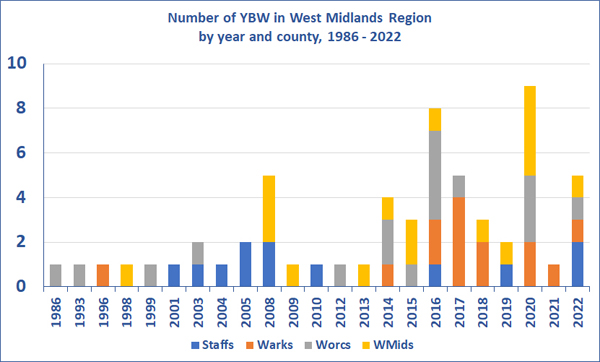

Figure 3 shows the annual distribution for the West Midlands Region as a whole, with individual totals for each of the four recording areas highlighted.

Figure 3. The annual distribution of Yellow-browed Warblers in the West Midlands Region between 1986 and 2022.

Two in a year were recorded for the first time in 2003 and five during 2008, a year which produced 486 nationally, at the time the second highest annual total on record (White & Kehoe 2014). Likewise, eight in 2016 coincided with a year which produced the highest ever national total at that time. A new high of nine reached the region in 2020. In the two subsequent years numbers fell back to one and five respectively, though BirdTrack trends show that once again this mirrors lower totals nationally. Thus, although there are exceptions (such as 2013, which produced the then third highest total nationally but only a singleton locally), peak years in the West Midlands region have broadly mirrored the national picture. Yellow-browed Warblers reached the region in every year between 2012 and 2022, with records in all four counties in 2016 and 2022.

The Regional total of 60 accredited individuals was distributed as follows: Staffordshire 12; Warwickshire 14; Worcestershire 17; West Midlands 17. This distribution perhaps hints at a slight southerly bias but is of doubtful statistical significance.

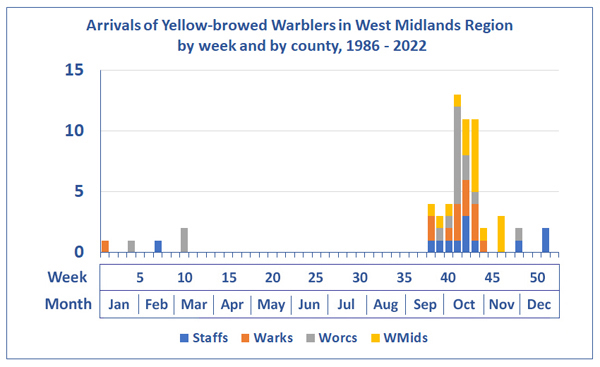

Figure 4. Weekly distribution of arrival dates of Yellow-browed Warblers by county.

Figure 4 shows the weekly distribution of arrival dates of Yellow-browed Warblers in the West Midlands Region, again highlighted by county. This distribution conforms broadly with the national distribution depicted in Figures 1 and 2 (from BirdTrack data), with records in the latter part of the year spanning mid-September to late-December but with a distinct peak during October. The middle of October was the peak time of arrival for Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire, with the fourth week of October for West Midlands. For the Region as a whole, 88% arrived during September to November, which compares with up to 97% nationally. Only 8.3% reached the West Midlands Region during the winter (defined here as December, January and February) and 3.3% during the spring (two in March). In addition, two individuals arriving on November 30th remained into December and January, respectively. Hence, slightly higher proportions were recorded in winter and spring than nationally, but autumn arrivals predominate throughout.

Table 1 shows the duration of stay for individual Yellow-browed Warblers reaching the West Midlands Region.

| Length of stay (days) | Number of Yellow-browed Warblers |

| 1 | 36 |

| 2 to 10 | 15 |

| 11 to 30 | 4 |

| 31 to 106 | 5 |

Table 1. Length of stay in days by Yellow-browed Warblers in the West Midlands Region, 1986 – 2022.

Details of the five longest-stayers are provided in Table 2. Three arrived between November 30th and January 27th while one arrived in spring (March 10th). The three arriving during the winter may well have arrived earlier farther north or east in Britain before moving on to the West Midlands Region. The longest stay, at Whittington, Staffordshire, in 2016 / 2017, involved 106 days, a remarkable three-and-a half months.

| Year | County | Location | Arrival | Departure | Number of days |

| 2016 | Staffs | Whittington | 16/12/2016 | 31/03/2017 | 106 |

| 2014 | Worcs | Uffmoor Wood | 27/01/2014 | 21/04/2014 | 85 |

| 2005 | Staffs | Baswich | 23/12/2005 | 10/02/2006 | 50 |

| 2012 | Worcs | Warndon | 10/03/12 | 21/04/2012 | 43 |

| 2019 | Staffs | Alrewas | 30/11/2019 | 01/01/2020 | 33 |

Table 2. The five longest-staying Yellow-browed Warblers in the West Midlands Region as at 2022.

The autumn arrival of significant numbers of Yellow-browed Warblers in Britain and Europe is now a well-established phenomenon. However, the reasons for this change are still not well-understood and nor is the destination and fate of the warblers involved.

High population levels and an expanding breeding range may well promote changes in post-breeding dispersal. Williamson (1975) discussed the involvement of climate change in the expanding breeding ranges of several species and wrote that: ‘The westwards expansion of a number of Siberian species has led to a greater frequency of vagrant appearances in Britain, particularly of the pioneering young birds in autumn’. However, such a radical increase in the numbers of Yellow-browed Warblers reaching Britain and western Europe implies that additional and more-fundamental changes have affected the migration strategy of a subpopulation of the species. In song-birds the migration strategy is genetically controlled. One frequently discussed theory is that errors in the ‘genetic compass’ are the underlying cause of movements in directions at variance with the standard direction. This includes the much-vaunted theories of reverse migration and mirror-image migration although, in some species prone to appear well outside their usual migratory range, neither concept appears compatible with their known movements (see Lees & Gilroy 2021). Also proposed are that magnetic anomalies can lead to increased vagrancy (Tonelli et al. 2023) and that juveniles deliberately undertake exploratory movements after leaving the natal area.

Whatever the underlying cause of radical departures from the standard direction of migration, it is suggested that an initially small number of individuals may fortuitously arrive in areas which provide a favourable wintering environment. Individuals which successfully over-winter and then return to their natal locations can pass on their novel migration strategy to their offspring. Over time (multiple generations) a sub-population migrating to the new wintering range becomes established (Gilroy & Lees 2003).

Given that transitory Yellow-browed Warblers in Britain and Europe are undertaking such purposeful movements, where are they headed? It was suggested by Gilroy & Lees (2003) that Yellow-browed Warblers might be en route to newly established winter quarters somewhere in southern Europe or west Africa. However, de Juana (2008) noted the relative paucity of Yellow-browed Warblers on spring migration through Europe and considered it more likely that juveniles, after undertaking exploratory movements in autumn, subsequently reoriented and returned to destinations in Asia. Additionally, were such a sub-population developing, then it should comprise increasing numbers of adults as well as juveniles. Yellow-browed Warblers are difficult to age but the perception is that most individuals reaching the west are juveniles, supported by studies of skull ossification conducted at Öland in Sweden by Magnus Hellström (Dufour et al. 2022). However, Tonkin & Gonzalez (2019) described a ringing recovery of a Yellow-browed Warbler in Andalucia which confirmed overwintering in consecutive winters.

Dufour et al. (2022) concluded that the current balance of evidence suggested that most Yellow-browed Warblers reaching Europe still comprised vagrants (i.e. individuals wandering outside their correct migration routes and wintering range and perhaps unlikely to reorientate successfully). Nevertheless, Yellow-browed Warbler provided an ideal model for studying the links between vagrancy and the emergence of new migratory routes. They proposed a collaborative series of research initiatives, intended to better clarify what remain intriguing questions.

Although increasing and including a handful of long-stayers, relatively few Yellow-browed Warblers remain in Britain into the winter, while spring occurrences are also rare (Figures 1 & 2). This contrasts with Siberian Chiffchaff P. (collybita) tristis, another Phylloscopus warbler which breeds from the Urals east across Siberia. The breeding ranges of the two taxa share some 75%. The traditional wintering quarters of Siberian Chiffchaff encompass northern regions of the Indian subcontinent (cf SE Asia for Yellow-browed Warbler). Siberian Chiffchaff has a long history of reaching Britain but its status here has been beset by uncertainties over its identification. However, a dedicated study into its status was initiated by the British Birds Rarities Committee (BBRC) during 2008 (Dean et al. 2010). Subsequently, between 2008 and 2019, records of Siberian Chiffchaff were included in the Report on scarce migrant birds published in British Birds, along with records of other scarce Phylloscopus including Yellow-browed Warbler. Developing trends in the numbers of Siberian Chiffchaffs recorded in Britain have no doubt been influenced by improving understanding of the taxon’s identification features but, notwithstanding, a distinct increase in numbers was detected during the twelve years during which the taxon was monitored, with around 120 in 2008, rising to over 500 in 2019 (White & Kehoe 2021). While most of those arriving in the north of Britain move on quite rapidly, matching Yellow-browed Warbler, farther south in England Siberian Chiffchaffs are established as a winter visitor in small numbers. Among individuals reported on the Birdguides website (www.birdguides.com) between 2001 and 2008, 44% were first detected between December and February (Dean et al. 2010), with higher proportions farther south. During the 2008 exercise, all but one individual arriving during December, January and February were south of a line approximately between the Severn Estuary and the Wash. Siberian Chiffchaffs are also now regarded as regular winter visitors in parts of Europe, in southern France and Italy among other countries.

Although in small numbers, Siberian Chiffchaff provides an informative example of wintering quarters becoming established in Europe, well remote from the traditional winter range in Asia. In this respect it draws parallels with the theories offered to explain the increasing numbers of Yellow-browed Warblers reaching Britain and Europe. However, while Yellow-browed Warbler is primarily a passage migrant in Britain, with relatively few remaining into winter, locations of winter quarters for tristis are reasonably well established in southern Britain and parts of Europe.

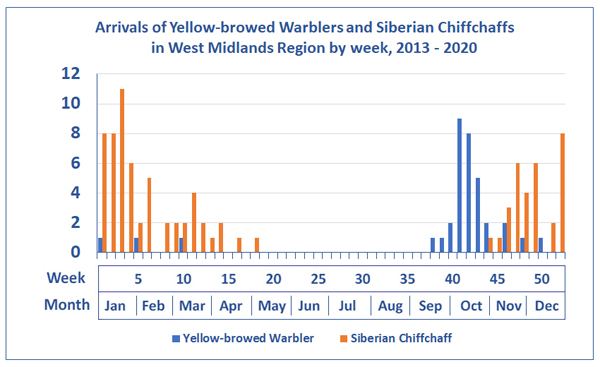

Nationally and including the West Midlands Region, Siberian Chiffchaffs begin to arrive about three weeks later than Yellow-browed Warblers but are then present in proportionately high numbers throughout the winter months. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution by week of arrival for the two taxa in the West Midlands Region during 2013 - 2020 (2013 marking the start of comprehensive tristis data in the WMBC Annual Reports). In the West Midlands Region during 2013 to 2020, just 8.5% of Yellow-browed Warblers were found during the winter months, December, January and February combined, compared with 70% of Siberian Chiffchaffs.

Figure 5. Arrivals by week of Yellow-browed Warbler and Siberian Chiffchaff in the West Midlands Region during 2013 - 2020.

During this eight-year period, 35 Yellow-browed Warblers were recorded at a total of 31 sites. At only two sites were individuals recorded in more than a single year (in two years at both Brandon and Earlswood). In contrast, 88 Siberian Chiffchaffs were recorded at a total of 24 sites, with individuals recorded in more than a single year at ten sites, notably Ladywalk (seven of the eight years), Hams Hall (6 years), Kempsey (five years), Lower Moor (five years) and Powick (four years). Thus, although only small numbers are involved, Siberian Chiffchaffs appear now to be deliberately selecting certain locations in the West Midlands Region as wintering quarters, with the vicinity of STWs especially favoured. While ringing returns would be needed to confirm the reappearance of given individuals in successive winters, this is supported by arrivals in repeat years at favoured sites and also the occurrence of a ‘mixed singer’ at Coton in successive years, 2014 and 2015 (deanar.org.uk/tristis/casestudy4.htm). Nationally, two tristis Chiffchaffs have been re-trapped in west Cornwall in successive winters (Grantham 2018), ‘adding to the evidence that these are returning wintering birds and not lost vagrants’ (Pomroy 2020).

The distinct monthly profiles of these two Siberian taxa support purposeful developments in their migration strategies yet also highlight differences in the timing and destinations involved in their evolving movements. These differences provide an intriguing topic and a stimulus for continuing studies. Yellow-browed Warbler and Siberian Chiffchaff now appear regularly in the West Midlands Region and observations here can contribute to on-going national and international research.

Without the frequently unsung enterprises of past and present editors, county recorders and their teams, in producing the WMBC Annual Reports, subsequent analyses such as this would be impossible. My thanks to them all. For information, discussion and other assistance during the preparation of this paper, I would like additionally to thank Scott Mayson (BTO), John Sirrett and Jim Winsper. The photograph of Yellow-browed Warbler at the head of the paper was provided by Pete Hackett.

Baker, J.K. & Catley, G.P. 1987. Yellow-browed Warblers in Britain and Ireland, 1968 - 85. Brit. Birds 80: 93 - 109.

Brown, A, & Grice, P. 2005. Birds in England. T. & A.D. Poyser, London.

Cramp, S. (ed.) 1992. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume 6. OUP, Oxford.

Dean, A., Bradshaw, C., Martin, J., Stoddart, A. & Walbridge, G. 2010. The status in Britain of ’Siberian Chiffchaff’. Brit. Birds 103: 320 - 338.

de Juana, E. 2008. Where do Pallas’s and Yellow-browed Warblers go after visiting northwest Europe in autumn? An Iberian perspective. Ardeola 55: 179 - 192.

Dufour, P., Åkesson, S., Hellström, M. et al. 2022. The Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus as a model to understand vagrancy and its potential for the evolution of new migration routes. Mov Ecol 10, 59. doi.org/10.1186/s40462-022-00345-2.

Dymond, J.N., Fraser, P.A. & Gantlett, S.J.M. 1989. Rare Birds in Britain and Ireland. T. & A.D. Poyser, Calton.

Gilroy, J.J. and Lees, A.C. 2003. Vagrancy theories: are autumn vagrants really reverse migrants? Brit. Birds 96: 427 - 438.

Grantham, M. 2018. West Cornwall Ringing Group. www.cornishringing.blogspot.com/2018/01/returning-sibe-chiff-kicks-off-2018.html

Harrison G.R & Harrison, J.V. 2005. The new Birds of the West Midlands. West Midland Bird Club.

Lees, A.C. & Gilroy, J.J. 2021. Vagrancy in Birds. Christopher Helm, London.

Pomroy, A. 2020. Chiffchaffs wintering at a sewage works in south Devon. Brit. Birds 113: 137 - 151.

Sharrock, J.T.R. 1974. Scarce Migrant Birds in Britain and Ireland. Berkhamsted.

Tonelli, B.A., Youngflesh, C. & Tingley, M.W. 2023. Geomagnetic disturbance associated with increased vagrancy in migratory landbirds. Sci Rep 13, 414. doi.org/10.1038/s41598022-26586-0

Tonkin, S. & Gonzalez, M.G. 2019. Ringing recovery of Yellow-browed Warbler in Andalucia confirms overwintering in consecutive winters. Brit. Birds 112: 686 - 687.

West Midland Bird Club. 1986 - 2021. West Midland Bird Reports 53 - 88. West Midland Bird Club.

White, S. & Kehoe, C. 2014. Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain in 2008 - 10. Brit. Birds 107: 251 - 281.

White, S. & Kehoe, C. 2016. Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain in 2013. Brit. Birds 109: 96 - 121.

White, S. & Kehoe, C. 2019. Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain in 2017. Brit. Birds 112: 639 - 660.

White, S. & Kehoe, C. 2021. Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain in 2019. Brit. Birds 114: 443 - 464.

Williamson, K. 1975. Birds and Climatic Change. Bird Study 22: 143 - 164.

Witherby, H.F., Jourdain, F.C.R., Ticehurst, N.F. & Tucker B.W. 1938. The Handbook of British Birds. Volume 2. Witherby, London.

Recommended citation: Dean, A. R. 2024. The status of Yellow-browed Warbler in the West Midlands Region and a comparison with Siberian Chiffchaff. https://deanar.org.uk/general/articles/ybw-wmidlands.htm

|

|